They do not represent all hazards and do not predict future conditions,” Michael Grimm, acting deputy associate administrator of FEMA’s Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration, told The Post. Maps only reflect past flooding conditions and are a snapshot in time.

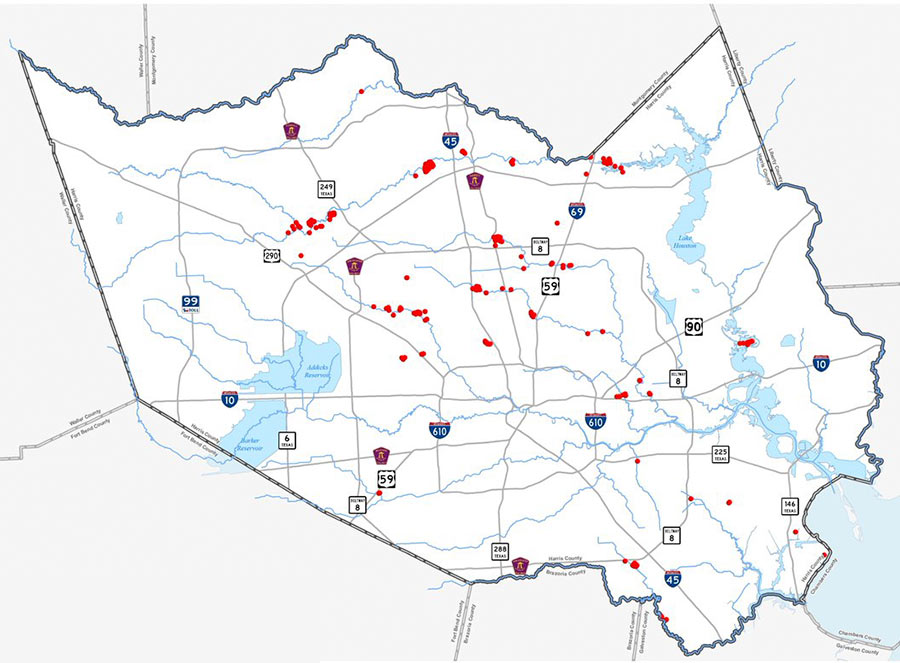

Fewer than 1 percent of single-family homes in these areas hold flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), the primary source of flood insurance for residential properties, according to an analysis of FEMA data conducted by the Seattle-based actuarial firm Milliman.įEMA officials have testified to Congress that over 40 percent of NFIP claims made in 2017 to 2019 were for properties outside official flood hazard zones, or in areas the agency had yet to map.įEMA stresses the maps are not meant to be predictive and that residents considering buying flood insurance should take into account other aspects of the overall risk to the property. Louis Dallas and Summerville, Ga., the maps fell short. In some instances, like the deadly July flooding in eastern Kentucky, the maps did convey higher risk where The Post verified visual material. The examination surveyed extreme flooding events between June and September across the country, by analyzing hundreds of videos and photographs, speaking with local residents, consulting experts, and interviewing local and federal officials. The resulting picture leaves homeowners, prospective buyers, renters and cities in the dark about the potential dangers they face, which insurance they should buy and what kinds of development should be restricted. As climate change accelerates, it is increasing types of flooding that the maps aren’t built to include. This 100-year flood plain designation requires property owners with federally backed mortgages to buy flood insurance, and it influences how communities regulate development.Ī Washington Post investigation uncovered communities throughout the country where FEMA’s maps are failing to warn Americans about flood risk. These high-risk zones, which lie in what’s called the Special Flood Hazard Area (SFHA), cover properties that the agency considers to have at least a 1 percent annual chance of flooding. Two days later, the area flooded all over again.īut Jones’s Penrose neighborhood isn’t designated as a high-risk location on the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s flood maps.

“Oh, my God,” Jones said in a video he posted to Facebook. Cars were barely visible under several feet of turgid storm water, as record rainfall fell on the city. Louis home was hit by major flooding for the second time since 2008, when he moved in.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)